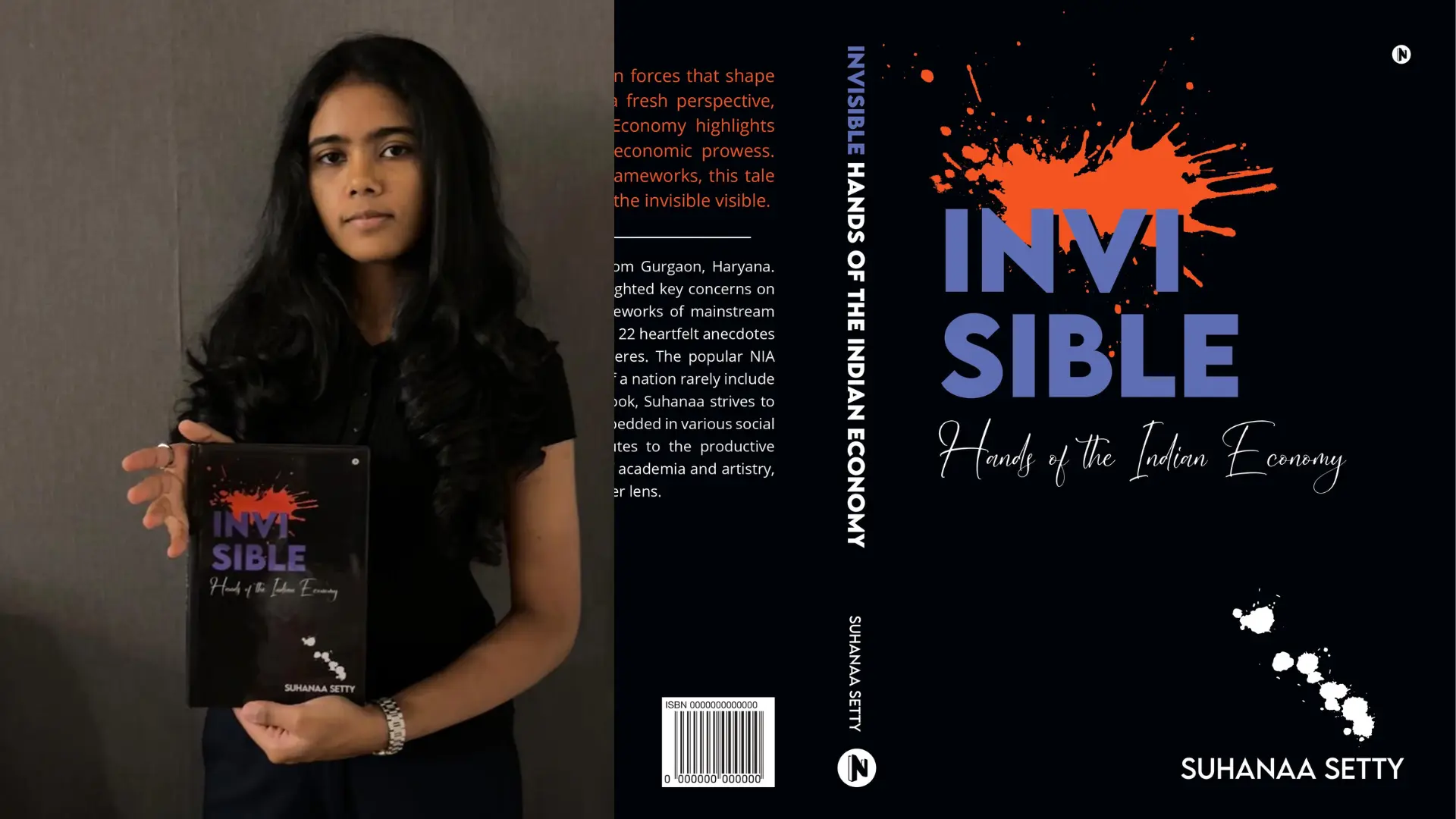

In a remarkable debut, 16-year-old Suhanaa Setty presents Invisible Hands of the Indian Economy, a book that sheds light on the often overlooked contributions of women in India’s economic landscape. Setty challenges traditional economic narratives that fail to recognize the essential, yet invisible, roles women play.

The book features the untold stories of 22 women from various walks of life—ranging from homemakers to laborers—whose significant contributions to the economy often go unacknowledged.

Invisible Hands of the Indian Economy encourages readers to rethink the concept of economic value, calling for a more inclusive measure of GDP that recognizes the unpaid work of women in areas such as household management, agriculture, and small-scale industries. Setty brings to life stories of women like Ratna and Parmila, who defy societal expectations and make invaluable contributions to their communities despite obstacles related to education and tradition.

What motivated a 16-year-old, to explore such a complex and underappreciated issue? Was there a particular moment or experience that drove you to write this book?*

The Author- Suhanaa Setty answered saying, “Growing up, I always wondered why my mother gave up her career to raise my sister and me. I used to ask her, “Why did you leave your job?” but her response was always a dismissive wave as if to say, “It’s not your concern.” But it was my concern. I needed to understand why raising us meant that my mother had to give up her independence and be confined to the house.”

She added saying, “As I got older, I began to grasp the larger social and economic dynamics behind her decision. My mother didn’t leave her job as a banker because she lacked skills or ambition; she did so because societal structures made it nearly impossible for her to continue working and care for us. She sacrificed her professional life, but that didn’t mean her contribution stopped. She was doing critical, unpaid work, like cooking and raising us, which ultimately impacts the economy, though it’s never counted in the GDP. My book captures these stories of invisible labor, showing how they are ignored by economists and policymakers alike.”

As the book highlights the critical yet overlooked role of women in India’s economy. In an economy driven by quantifiable data, what needs to happen for policymakers to take women’s unpaid labor seriously? Is there any willingness to redefine economic value to include this contribution?*

It’s clear that our policies and economic frameworks need to evolve to account for the unrecognized labor force. Collecting relevant data on unpaid labor should be the first step, but that requires political will and leadership. Our leaders must emphasize the importance of gender equality in economic policy. Once that happens, industries and corporate sectors will follow suit.

Investing in the education and training of women is crucial. It’s not just the government’s responsibility; NGOs and private sectors need to collaborate to elevate the visibility of unpaid women’s labor. While some initiatives exist, they are not enforced rigorously, and the framework for addressing these issues is outdated. The barriers are a lack of clear directives, political will, and educational incentives for women.

How exclusion affects the broader discourse on gender equality and economic justice in India?

Suhanaa replied, “Excluding women’s unpaid labor is a form of economic injustice, which contributes to the suppression of women and strips away their independence. Correcting this imbalance is not just about economic growth; it’s about fostering social change and inclusivity. Recognizing unpaid labor would allow women to be seen as financially independent contributors to society.

Moreover, not accounting for this labor skews our understanding of productivity and economic growth. If we address this issue, we can create a more accurate representation of the economy and, at the same time, drive meaningful social progress.”

The book advocates for expanding the definition of GDP to include unpaid work such as household management and small-scale agriculture. How economists and policymakers will react to this idea?

Any suggestion for change will naturally face resistance. Traditional economists may argue that measuring unpaid labor is challenging and that restructuring the GDP framework will be complicated. Policymakers may resist systemic changes. However, I believe there will also be a group of people who will recognize the necessity of this inclusion—especially those advocating for gender equality and fair representation of labor.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on the critical roles played by caregivers and essential workers, many of whom are women performing unpaid work. This global recognition may pressure governments to adopt measures that finally recognize this invisible workforce and incorporate it into our economic indicators.