The concept of waqf, an Islamic endowment, has played a pivotal role in preserving wealth and supporting charitable causes for centuries. Among its various forms, waqf-alal-aulad stands out as a unique system that ensures financial security for the descendants of the donor while sometimes contributing to public welfare. This article explores the historical significance, legal framework, and contemporary relevance of waqf-alal-aulad, particularly in India and other Islamic nations.

What is Waqf-alal-Aulad?

Waqf-alal-aulad is a private form of waqf where the revenue generated from an endowed property benefits the donor’s family members. Unlike public waqf, which is dedicated to religious or charitable purposes such as funding mosques, schools, or supporting the needy, waqf-alal-aulad primarily secures financial stability for a donor’s lineage. However, donors can also include provisions in the waqf deed to allocate a portion of the income for charitable activities.

Historical Context and Evolution

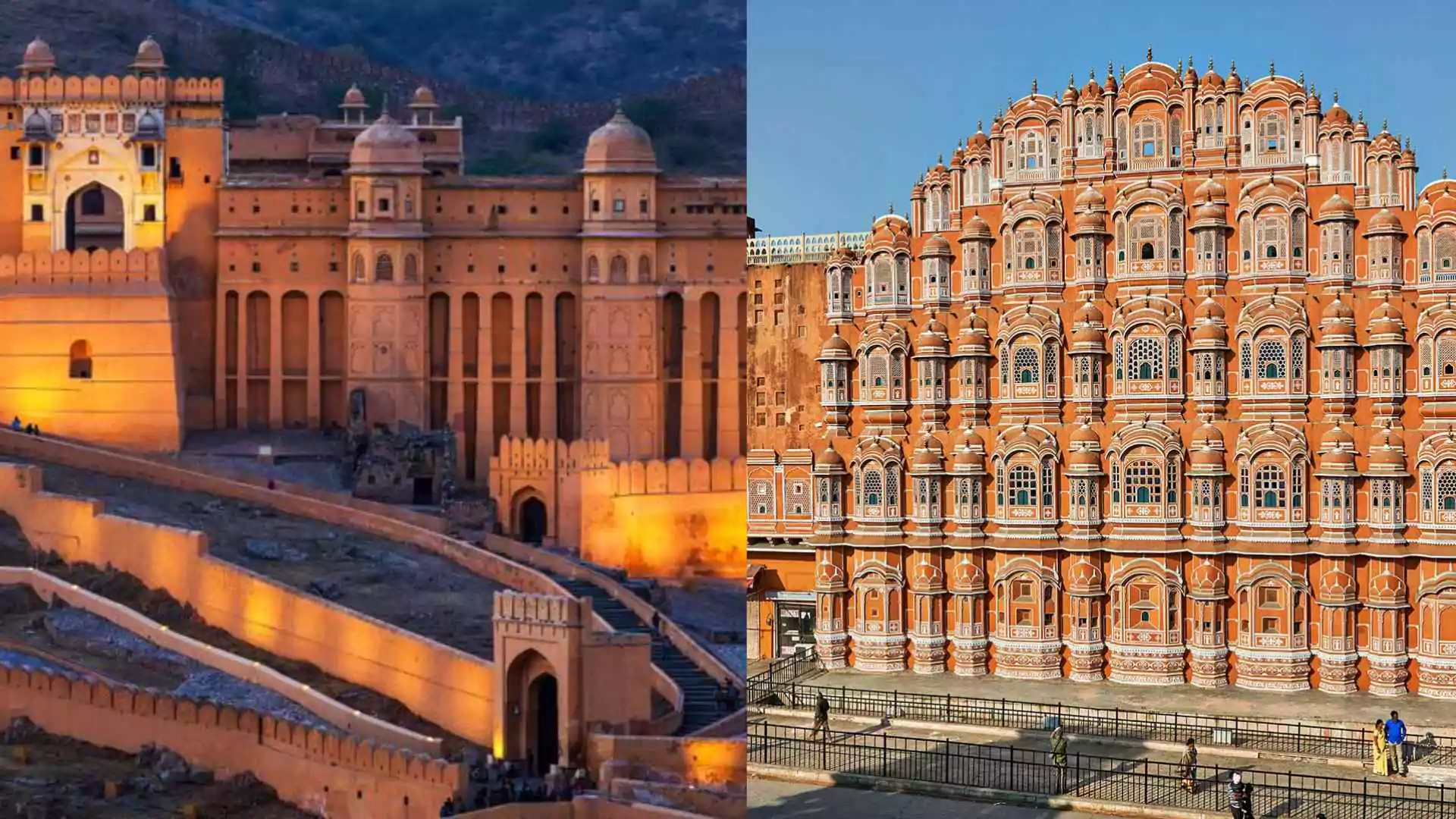

The tradition of waqf-alal-aulad gained prominence during the Ottoman Empire, where it became a strategic tool for wealth preservation. By transferring assets into waqf, affluent families shielded their wealth from fragmentation due to inheritance laws or state confiscation. Similarly, in Mughal India, several noble families and regional rulers, such as the Nawabs, employed waqf-alal-aulad to safeguard their estates for future generations.

Even in modern times, wealthy individuals in Gulf nations continue to use this practice to ensure their businesses and properties remain within the family while maintaining economic stability across generations.

Legal Status and Challenges in India

In India, waqf properties hold significant legal standing, governed by various laws enacted over the years. However, waqf-alal-aulad often sparks debates due to potential conflicts with Islamic inheritance laws (Sharia), which dictate fixed shares for heirs. Critics argue that this system allows property owners to bypass inheritance rules, raising concerns about fairness and legal loopholes.

To enhance transparency, the Indian government has introduced The Waqf (Amendment) Bill, 2025, which aims to streamline waqf property management, improve governance, and strengthen the role of Waqf Boards. Additionally, the Mussalman Wakf (Repeal) Bill seeks to eliminate outdated colonial-era laws to ensure efficient administration.

Notable Examples of Waqf-alal-Aulad

- Ottoman Empire: Wealthy landowners used waqf-alal-aulad to maintain their estates across generations while preventing state appropriation.

- Mughal India: Nawabs and aristocrats established waqf-alal-aulad to secure their families’ economic well-being.

- Modern Gulf States: Business tycoons continue to set up family waqfs, ensuring their enterprises remain within their bloodline.

Can Waqf Properties Be Taken Back?

Once designated as waqf, a property is considered perpetual and irrevocable. This means it cannot be sold, transferred, or reclaimed. For instance, the Bengaluru Eidgah ground has been recognized as waqf property since the 1850s, and similar cases exist across India where municipal buildings and other assets are claimed as waqf properties due to historical usage.

While India has a well-established Waqf Board system, not all Islamic countries follow this practice. Nations like Turkey, Egypt, Libya, and Syria have moved away from the traditional waqf system, whereas in India, Waqf Boards remain among the largest landowners, with legal safeguards ensuring their continuity.

The institution of waqf-alal-aulad remains a powerful tool for wealth management, balancing religious, familial, and societal interests. However, its legal implications continue to evolve, especially in countries like India, where governance reforms aim to modernize waqf administration. With new legislative measures on the horizon, the future of waqf-alal-aulad will be shaped by efforts to balance tradition with transparency and fairness in wealth distribution.

ALSO READ: Asaduddin Owaisi Tears Waqf Bill In Lok Sabha: Says ‘Like Gandhi, I Reject This’